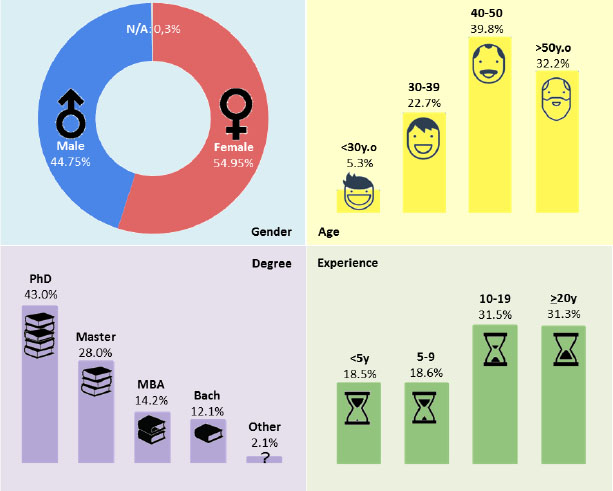

Figure 1. Participants’ profile.

COVID-19, Changes in Educational Practices and the Perception of Stress by University Educators in Latin America – a Post-pandemic Analysis

COVID-19, Cambios en las prácticas educativas y percepción del estrés por parte de los educadores universitarios en América Latina – un análisis post pandémico

Ismar Frango-Silveira*a, Renata Mendes-de-Araújob, Valéria Farinazzo-Martins c, Maria Amelia Eliseod, Cibelle Albuquerque-de-la-Higuera-Amatoee, Ana Casalif, Diego Torresg, Vladimir Costas Jaureguih, César Collazosi, Darwin Muñozj, Cinthia de la Rosa-Felizk, Nilda Yangüez-Cervantesl, Klinge Orlando Villaba-Condorim, Manuel J. Ibarra-Cabreran, Virginia Rodés-Paragarinoo, Regina Motzp, Maria Viola de Ambrosisq, Antonio Silva Sprockr

a Mackenzie Presbyterian University / Cruzeiro do Sul University, São Paulo, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8029-072Xismar.silveira@mackenzie.br

b Mackenzie Presbyterian University / São Paulo University / National School of Public Administration, São Paulo, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8674-1728renata.araujo@mackenzie.br

c Mackenzie Presbyterian University, São Paulo, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5058-6017valeria.farinazzo@mackenzie.br

d Mackenzie Presbyterian University, São Paulo, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0913-3259mariaamelia.eliseo@mackenzie.br

e Mackenzie Presbyterian University, São Paulo, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2422-6998cibelle.amato@mackenzie.br

f National University of Rosario, Rosario, Argentina

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0737-5246acasali@fceia.unr.edu.ar

g National University of La Plata, La Plata, Argentina

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7533-0133diego.torres@lifia.info.unlp.edu.ar

h Higher University of San Simón, Cochabamba, Bolivia

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5917-3035vladimircostas.j@fcyt.umss.edu.bo

i University of Cauca, Popayán, Colombia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7099-8131ccollazo@unicauca.edu.co

j Federico Henríquez y Carvajal University, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4691-2614dcmunozn@gmail.com

k Federico Henríquez y Carvajal University, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9696-4132cinthiadelarosa@outlook.com

l Technological University of Panama, Panama City, Panama

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5251-9769nilda.yanguez@utp.ac.pa

m Continental University, Arequipa, Peru

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8621-7942kvillalba@continental.edu.pe

n Micaela Bastidas National University of Apurímac, Abancay, Peru

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6711-4916manuelibarra@gmail.com

o University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7229-4998virginia.rodes@cse.udelar.edu.uy

p University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1426-562Xrmotz@fing.edu.uy

q University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0134-4852mvdeambrosis@gmail.com

r Central University of Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9911-4774antonio.silva@ciens.ucv.ve

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about profound changes in social and professional contexts. Schools and universities all over the world were closed to curb the contamination. In a short period, many educators were forced to reinvent their classes in a non-classroom mode, mediated by technology. This scenario of overwork can lead educators to stress, favoring distress, anxiety, and depression due to the uncertainties resulting from the pandemic and the search for new knowledge acquisition. This paper shows the research results conducted by university educators in Latin America who have been exercising teaching activities during social isolation imposed by COVID-19. The results show that with just one exception, educators from all countries reported suffering from some stress-related aspects concerning some manner to remote teaching. Higher workload perception came from women, unfolding gender inequalities amplified during pandemics. There is no clear relationship between the degree of technological expertise and stress factors, although, in general, educators use more time to prepare learning material and monitor students’ progress. Technological infrastructure was not a big concern for those educators in big cities, but some fundamental infrastructure problems were reported due to each country’s economic reality or geographic conditions.

Keywords

COVID-19, online education, higher education, stress.

RESUMEN

La pandemia de la COVID-19 provocó profundos cambios en los contextos sociales y profesionales. Se cerraron escuelas y universidades de todo el mundo para frenar el contagio. Muchos educadores se vieron obligados a reinventar sus clases en un modo no presencial, mediado por la tecnología en un corto período de tiempo. Este escenario de exceso de trabajo puede llevar a los educadores al estrés, favoreciendo el malestar, la ansiedad y la depresión por las incertidumbres derivadas de la pandemia y la búsqueda de nuevos conocimientos adquiridos. Este artículo muestra los resultados de una investigación realizada con educadores universitarios en América Latina que han venido ejerciendo la actividad docente durante el aislamiento social impuesto por la COVID-19. Los resultados muestran que, con una sola excepción, los educadores de todos los países informaron sufrir algunos aspectos relacionados con el estrés en relación con alguna forma de enseñanza a distancia. Las mujeres percibieron una mayor carga de trabajo, lo que generó desigualdades de género amplificadas durante las pandemias. No existe una relación clara entre el grado de experiencia tecnológica y los factores de estrés, aunque, en general, los educadores emplean más tiempo para preparar material de aprendizaje y monitorear el progreso de los estudiantes. La infraestructura tecnológica no era una gran preocupación para los educadores en las grandes ciudades, pero se informaron algunos problemas fundamentales de infraestructura debido a la realidad económica de cada país o las condiciones geográficas.

Palabras clave

COVID-19, educación en línea, educación superior, estrés.

1. Introduction

More than two years after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and after many imposed periods of social isolation, in the so-called “post-pandemic” period, many challenges are still identified in acting and interacting professionally and socially through technologies. Although online interaction technologies are not new to many, the requirement imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased their use (Hew et al., 2020). It is expected that the COVID-19 pandemic may trigger a series of individual and specific policy changes around the world (Novaes & Aquino, 2021) and their psychosocial impacts are still to be fully understood.

In this emerging public health scenario, the face-to-face activities of educational institutions were interrupted and started to be performed through digital resources. The educator, considered an essential agent of this process, found himself abruptly and urgently responsible for significantly altering his pedagogical practice. The unprecedented changes in educational practices (Fardoun et al., 2020) and the uncertain future give room for discussing educators’ mental health (Sahu, 2020). Anxiety and depression, exacerbated by uncertainties, a fierce search for knowledge acquisition and the information flow´s intensification should significantly increase this process, bringing negative physiological consequences, such as stress (Gómez-Gómez et al, 2022).

In this paper, we present the results of a survey with higher education educators in Latin America, aiming to understand the stress factors related to the urgent changes in teaching practices resulting from the pandemic. The survey was conducted through an online questionnaire, answered by 1010 university educators who have been teaching during social isolation imposed by COVID-19. The initial survey comprised respondents from Argentina (52), Bolivia (24), Brazil (451), Chile (13), Colombia (19), Costa Rica (6), Ecuador (2), Mexico (2), Panama (15), Paraguay (3), Peru (48), The Dominican Republic (76), Uruguay (232), Venezuela (20). From these, countries without a significant number of respondents were not submitted to qualitative analysis.

The collected data were submitted to qualitative and quantitative analysis to help us understand: a) the occurrence or not of signs of stress among higher education educators during the period of isolation and migration to remote classes; and b) the relationships among the levels of signs of stress and other variables related to a personal profile, teaching performance, isolation context, experience with tools and methods for online teaching and work relationships. Data resulting from the survey suggests stress factors among educators involved in remote activities during the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing gender.

The paper is organized as follows: the next session discusses related work on the subject, while section 3 explains the scientific method underpinning this article. The fourth section analyzes all data gathered, related to the stress factors related to teaching conditions in pandemic times. Section 5 details specific points per each participating country. Section 6 discusses the main findings based on data analysis and, finally, conclusions are presented in Section 7.

2. Related Work

Higher Education Institutions gave different answers to the emergency brought by COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Knopik and Oszwa (2021) and Rodríguez-Paz et al. (2021) discuss some specific strategies taken during pandemic times in different context. However, most of the institutions worldwide adopted, for some time, synchronous remote teaching as an alternative to face-to-face classes, meetings, and the supervising processes, which allowed professors to carry out their academic activities in a brand-new context. In this sense, an already stressful situation, caused by the limitations imposed by COVID-19, was potentialized by the work-related context brought to professors’ homes.

Odriozola-González et al. (2020) conducted a survey on symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress at the University of Valladolid, Spain, during the first weeks of confinement, collecting data from collecting data from 2,500 respondents (335 teachers). Educators from the Arts and Humanities fields showed significantly higher scores on the depression, anxiety, and stress scales, followed by educators from the Health, Science and Social Sciences and Law fields, and finally, educators from the Engineering and Architecture.

Huang and Zhao (2020, 2021) analyzed data from a national survey conducted in China to assess the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of workers in general. From the 7,236 respondents to the questionnaire, 1,404 were educators (university, high school, and primary education). 35.1% of the educators presented anxiety symptoms, 21% had depression and 14.3 reported problems in sleep quality.

Pather et al. (2020) carried out a qualitative study with 18 anatomy educators from 10 universities in Australia and New Zealand during pandemic. Respondents reported that although they remained focused on pedagogical issues, the expectations, and skills to develop them had changed, mainly about training and appropriate use of technologies. Respondents also reported concerns about the sustainability of their jobs, due to budget cuts and the significant increase in the workload for preparing educational material.

Monteiro and Souza (2020) conducted a literature review of publications between 2017 and 2020 to identify the effects of the transition to remote education and the social isolation caused by the pandemic on educators’ working conditions and mental health. Although the research did not focus on a specific country or region, the analysis was discussed from the Brazilian context. They conclude that the precariousness of teaching work was already a reality before the pandemic, intensified by changes due to pandemics. Moreover, the demands regarding pedagogical and evaluation aspects, learning paradigms, and adequacy to information technologies have increased. A similar analysis is brought by Pereira et al (2020) and Robinet-Serrano and Pérez (2020).

Zeeshan et. al. (2020) highlights the issues faced by the university faculty of 16 universities in Pakistan, regarding techno-stress due to a lack of pandemic preparedness, through a qualitative study based on interviews. Their findings show that most faculty educators felt overburdened with additional responsibilities about online teaching besides their efforts.

The - sometimes abrupt - return to face-to-face activities in unprecedented teaching situation caused also significant impacts on teachers’ well-being and quality of life, as discussed by Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2021) and Lizana et al. (2021), as well as the impact on universities, which remains an open question to be verified in the next years (García-Peñalvo et al., 2021a).

3. Method

3.1. Participants

The survey involved nine countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, surveying 1010 university educators, who have been in social isolation imposed by COVID-19 – a convenience sample. Invitations to participate were made via social networks and lists of participants from scientific societies. The Research Ethics Committee of the leading institution approved the study (CAEE: 31159320.8.0000.0084) and all ethical principles were respected.

3.2. Procedures

The online questionnaire, used as an instrument of data collection, allowed reach and agility in data collection, considering the limitations imposed by the pandemic of COVID-19. This questionnaire was developed and applied in a previous study carried out in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Brazilian reality (Araujo et al., 2020).

The questionnaire was self-explanatory and took an average of 10 minutes to be answered. The data were obtained between May and June 2020. It should be noted that the questionnaire was prepared and made available via Google Forms in all participating countries except Uruguay, which used another platform due to the country’s data protection policy and because more than 50% of active university educators in the country are in the same Higher Education Institution which required some adjustments to the instrument to meet the local reality.

3.3. Limitations

In this research, convenience sampling was used with higher education educators working in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, not all Latin American countries entered this sample. Some did not respond to the invitation, and others could not carry out a significant collection that could generate results, such as Ecuador and Mexico, which had only two respondents. There was no uniformity in the number of participants per country, while in Brazil and Uruguay there were more than 200 respondents, 451 and 232, respectively, other countries did not reach 20. Panama, for example, presented its results with only 15 respondents.

It is noteworthy that the data were collected at the beginning of the pandemic when the countries participating in this research were still starting remote education. It is possible, over time, that the stress of higher education educators may have changed due to adaptation to technologies or tiredness of so much time in isolation.

4. Analysis

This section presents the responses obtained by the collection instrument, according to the expected dimensions of analysis.

4.1. Participants’ profile

From the 1010 participants who responded to the survey, 555 identified themselves as female (close to 55%), 452 male (close to 45%) and 3 participants did not want to inform the gender. Regarding age: 5.3% are under 30 years old, 22.7% are between 30 and 39 years old, 39.8% are between 40 and 50 years old and 32.2% answered to be over 50 years old. Most respondents (71.7%) have graduate degrees (43% said they had Ph.D. / Post-Doc while 28.7% had a Master’s degree), 14.2% had post-graduation (MBA-like), 12.1% had only a degree, and 2.1% declared others. Regarding teaching experience, most respondents (62.9%) have more than ten years of teaching experience: 18.5% are less than five years, 18.6% between five and nine years, 31.6% between 10 and 19 years and 31.3% are 20 years or more. These data are summarized in the infographic in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Participants’ profile.

During the pandemic, 27.9% declared they were not having remote experience, 67.8% were having some remote activity and 4.3% opted for N/A. Of the 1010 participants (initial survey population), 103 (about 10% of the initial population) said they were not doing the remote activity. These data were taken from the survey, as they did not answer the rest of the questions. Thus, from here, 907 respondents will be considered as the total number of research participants.

Other important data gathered from the survey are: 82.4% of the participants declared to be living with the family during the pandemic, 11% alone, 5.9% opted for "others" and 0.7% for N/A. 60.4% of these participants live in large cities (more than 500 thousand inhabitants), 9.9% in medium-big cities (300-500 thousand inhabitants), 15.9% in medium-sized cities (100-300 thousand inhabitants), 7.2% in medium-small cities (50-100 thousand), 5.3% in small cities (less than 50 thousand inhabitants) and 1.2% chose N/A as the answer option. Regarding computer devices, 73.2% reported having exclusive use equipment, 15.7% shared use and 11.1% did not have or chose N/A as the answer standard.

4.2. Experience in online teaching and use of technologies

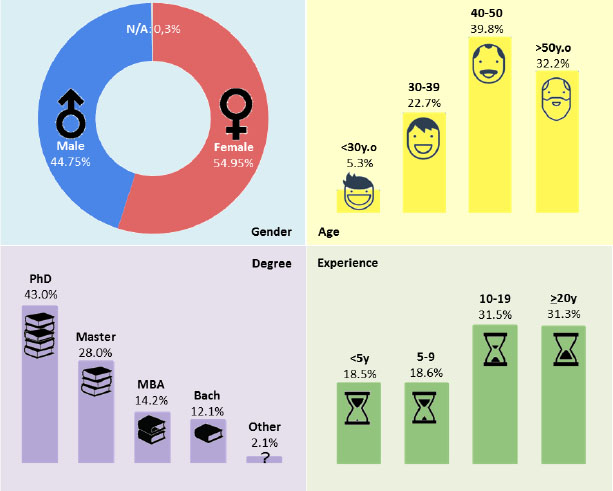

Regarding previous remote teaching experience before the pandemic, 35,5% declared that they had never had it, while 60.2% had already had some experience and, still, 4.3% declared N/A. About their skill level with the use of equipment (computers, tablets, or smartphones) and software in general, a large majority (59.4%) declare themselves to have high or very high skill, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Experience with technologies and software in general.

When asked if the equipment and internet access they had was sufficient to carry out their remote activities, the vast majority (87.2%) of the participants said they had adequate equipment and internet access (87.9%). On the other hand, it was found that only 26.4% said they had acquired some type of technology to exercise their remote activities.

When asked about difficulties in using technologies and software, 45.3% of respondents stated they had difficulty, representing almost half of the participants. Among the most acquired technologies are: equipment (computer, notebooks) and updating equipment; video conferencing systems, such as Zoom; higher speed internet; peripheral equipment, such as graphics tablet, microphone, headphones, mouse, digital whiteboard, webcam; software such as screen recorders, video editor.

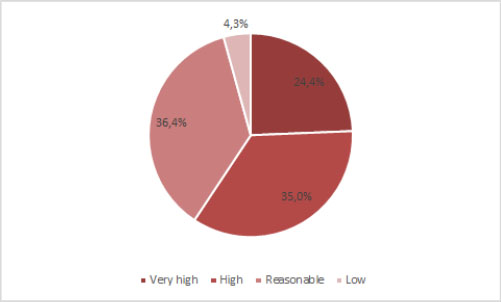

4.3. Perception of stress

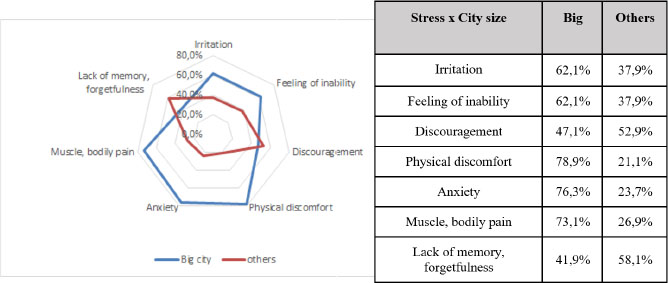

Regarding the seven variables that may indicate stress, the following results were found in Figure 3. The most impacted variable perceived by the participants was physical discomfort (48,30%), followed by anxiety (47%) and muscle, bodily pain (44 %).

Figure 3. The seven dimensions of stress.

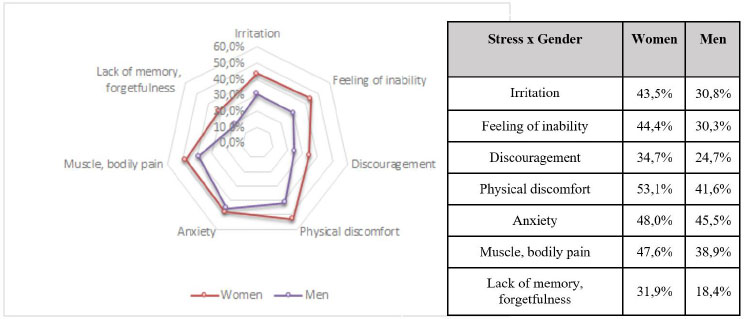

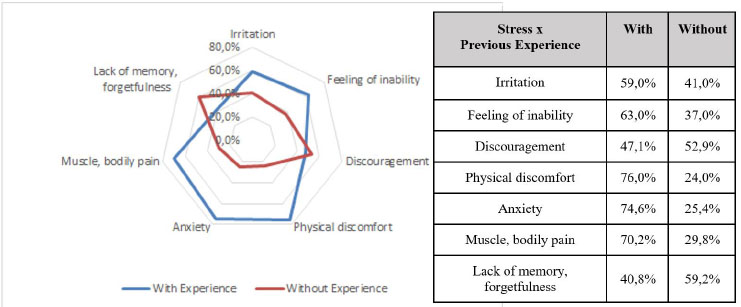

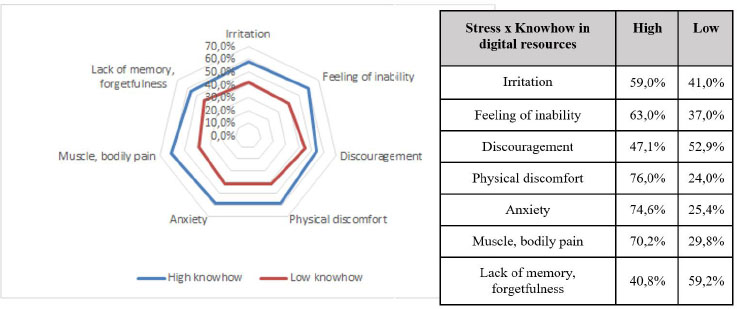

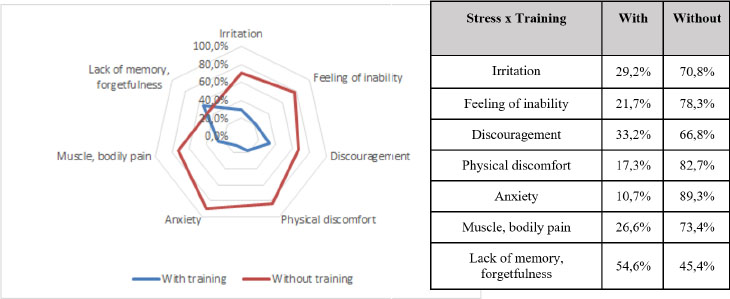

These dimensions were also related to gender (Figure 4), previous experience in technology-mediated education (Figure 5), ability with technology (Figure 6), training before and during social isolation (Figure 7), size of the participants’ city (Figure 8).

Figure 4. Stress x Gender.

Figure 5. Stress x Experience in technology-mediated education before confinement.

Figure 6. Stress x Knowhow in digital resources.

Figure 7. Stress x Training.

Figure 8. Stress x City size.

There is a marked predominance in the perception of female educators’ stress factors to male ones. Studies show that women have more symptoms of stress than men. There are indications, according to studies, that this more significant stress may be related to the accumulation of household functions (care for the home and children), usually associated with women in societies in which there is a solid macho cultural component, as is the case in many countries in Latin America (Goulart Junior & Lipp, 2008; Martins, 2007; Sadir et al., 2010).

On the experience with remote education before the pandemic and know-how about technologies and resources, there is a predominance of stress in educators who already had experience/had know-how about technologies, which, at first glance, might seem strange. However, these educators probably had some experience, they knew a little about the digital platforms and resources, but they experienced the continuous use of these platforms and then, the problems that arose were: unstable internet connection, overload of digital platforms, among others, that made the experience frustrating. On the other hand, according to Figure 7, it seems that training in the use of platforms and digital resources was a gain for educators, since they were the ones who reported lower stress levels.

Regarding the size of the participants’ living cities, stress is more evident in people living in big cities in five of the seven dimensions. This may be related to the lifestyle and urbanism itself. People who live in large cities generally live in smaller apartments or houses, with a non-existent or reduced leisure area, more significant mobility difficulties, and higher living costs.

5. Main Considerations by Country

5.1. Argentina

In Argentina, classroom activities were suspended from March 20th, 2020. University authorities and educators have been making great efforts to continue higher education virtually. Most respondents are women (61%) from the central region of the country and reside in large cities. They have extensive teaching experience in higher education, mainly in public education, and most of them work in the STEM area.

The stress factors reported with a greater degree of impact have been “muscle and body aches” and “anxiety”. Women have shown a higher percentage of worsening of body pain symptoms, while men have reported a somewhat more significant impact on anxiety. Stress aspects are linked to other information gathered in the survey. Most of the educators (over 50%) have answered the categories workload and lack of personal time with “much” or “extremely”, respectively. Besides, they qualified with the same intensity the excessive overlapping of household tasks that usually loads more heavily on women since in Argentine society, the work burden is often not distributed in an egalitarian way at home (Goren et al., 2020).

It should be noted that a significant percentage (62%) expressed having worsened in one or more of the aspects related to stress. Regarding other emotions, the categories that appear most are “tiredness” and “anguish”. There is tangible evidence that stress on Argentine university educators has increased in the COVID context, as can be seen in other reports (COAD, 2020; UNICEF, 2020).

Concerning self-perception of skills in digital technologies, the results show a contrast in a high level of management of technologies (most of the educators are in STEM – Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (García-Peñalvo et al., 2022; García-Holgado et al., 2022)) compared to the difficulties encountered in using them in teaching (nearly 50% expressed difficulties). Surprisingly, few seem to have sought help. According to the survey, the use of teaching tools outside the physical space in the classrooms posed several challenges for many of the people surveyed. Reflections were expressed from a positive perspective of the situation that initially demanded hard work. They say it was confusing, but “finally, worthy”. On the other hand, several educators have considered that the amount of work increased notably, generating stress and burnout.

Beyond the challenges of using technological tools, most of educators adapted their classes to be performed virtually. According to the people surveyed, this situation generates a change in the educator-student relationship. They indicate that the relationship in the physical classroom “is not replaceable by the virtual one” since “empathy with the student is difficult to achieve”. However, the difficulties in communication or the number of complaints from students have remained low; they seem to have understood that the present difficulties are typical of abrupt change. A detailed report on Argentinian situation can be seen in Casali and Torres (2021).

5.2. Bolivia

From March 12th, 2020, Bolivia begins social distancing due to COVID-19. In the first three months, the distancing has strict measures that force citizens to stay at home six days a week, going out to refill for one day in the morning. Social distancing persists in Bolivia; however, regulations have been made more flexible due to the population’s needs.

The survey was disseminated by institutional mail at the Universidad Mayor de San Simón and through friendly educators in four other Bolivian universities. Only 23 educators responded to it. Based on the observed results, it is presumed that these educators could represent a select group of educators active in using ICT in higher education.

The results show that all educators work in universities (all public) that suspended activities during isolation. Most had previous experience in virtual classes; they have adequate computer equipment for their work and access to an internet connection that covers the requirements to carry out virtual classes. More than 60% indicate that they have high skills in handling computer equipment and related software. The educational tools that prevail among the respondents are Moodle, Google Classroom in the case of LMS. For video conferencing, the most common are Jitsi, Google Meet and Zoom. Note that Bolivian educators seem to prefer free educational tools.

In the psychological-emotional and physical aspects, findings show that female educators reported greater susceptibility to physical manifestations during social isolation - more than 60% of female educators report feeling discomfort compared to 40% of their male colleagues. Women educators present higher physical discomfort, muscle pain and memory failure; while men present higher manifestations such as irritation, discouragement, and anxiety.

Most educators consider they work more at home than at the office during social isolation. The workload perception is noticeably more significant in women. Besides, the workload of the office and domestic tasks is considered double shift by most of the educators, being noticeably higher in women. Likewise, less than 50% of men consider that personal time is insufficient. While, in the case of women, the vast majority consider that they do not have a time of their own.

Most educators consider that the dialogue with their superiors has deteriorated. Women have a perception that the home environment is not appropriate for work; Men do not have the same perception, and it is undoubtedly due to attention to housework. Also, most women feel more insecure about their job position than men; this perception is because women are more likely to lose their jobs due to “macho culture” still present in Bolivian society.

5.3. Brazil

The first case of COVID-19 in Brazil was reported at the end of February 2020, as we followed the progress of the pandemic in China and the countries of Europe. The São Paulo city became the epidemic epicenter in the country, registering its first death in mid-March. Before the end of the same month, all Brazilian states already registered confirmations of infected citizens. In one month, the epidemic reached the entire national territory. The data presented by the Brazilian educators who participated in the survey demonstrate that the perception of stress is strong among higher education educators in Brazil who remained in remote education activity during the social isolation resulting from the pandemic.

There is a marked predominance in the perception of stress factors in female educators, some symptoms are related to aspects of their own physiology such as pimples, pelvic pain, dry skin, menstrual cramps (Calais et al., 2003). Besides, there are factors related to the accumulation of domestic functions (care for the home and children), generally associated with women in societies where there is a solid macho cultural component - such as the Brazilian one (Goulart Junior & Lipp, 2008; Martins, 2007; Sadir et al., 2010). Stress factors are more present in educators who work in Social and Legal Sciences courses, followed by educators in Health Sciences fields, and less present in Arts and Humanities, who work in more than one field.

There is a strong inverse correlation between stress factors and the self-perceived ability with digital technologies, especially concerning discouragement and the feeling of incapacity - the latter factor may be due to insecurity for the full use of digital technologies in the educator teaching-learning process. Still, it can also point to a need for improvement in the user experience currently provided by the most used tools. In addition, there is a great expectation about the appropriate use of technology and its availability, on the part of educators, which often was not matched due to the infrastructure of the educational institution that was not prepared for such a huge demand, leading them anxiety and reinforces discouragement and the feeling of incapacity (Poalses & Bezuidenhout, 2018; Pather et al., 2020; Sahu, 2020).

A more comprehensive analysis of Brazilian situation can be seen at Araujo et al (2020).

5.4. Colombia

In the case of Colombia, there were 20 answers mainly from the Southwest region from the public and private institutions with more than five years of experience in teaching-learning processes. All the surveyed educators revealed they have computers in their homes and with a good internet connection. One of the most complicated situations was regarding the lack of methodological models supporting teaching in COVID time.

Most surveyed people have reported that excessive stress (Pedrozo-Pupo et al., 2020), especially when they have little or no control, can cause health, mental, and physical problems. Managing a new teaching style, disruptions to research and writing practices, and the realities of working from home have proved to be a dramatic task for many of them. Most of the surveyed educators manifested that, during the COVID-19, they have experienced a range of emotional reactions: frustrated, overwhelmed, stressed, and tired. In the psychological-emotional and physical aspects, findings show surveyed people reported greater susceptibility to physical manifestations during social isolation. This is causing significant disruptions to their schedule, due to educators being asked to do a lot of work related to the transition to online instruction in a short time while also feeling anxious about their family and community.

The responses have revealed some positive aspects during the COVID-19 Pandemic: most educators continued to teach, non-digital content became digital, and several educational institutions transitioned all their operations from traditional face-to-face to online teaching. According to the survey, there was no difference in relation to stress factors with educators who have received any training in digital technologies in teaching before or due to the pandemics.

5.5. Dominican Republic

In the Dominican Republic, 79 university educators from different provinces participate in the study. 92% of the educators surveyed confirmed that they have a computer for exclusive use at home, and 78.50% admit having a good internet connection that allows them to carry out their work activities. Due to the protection measures against the COVID-19 pandemic and during the months of home confinement, great difficulties were identified with the methodology for remote teaching: 47% admitted having methodological limitations, even though 63.3% of the educators recognized that the university where they work provided training on the use of technological tools for remote teaching before the social isolation and 73.42% during the quarantine.

We did not find high degrees of irritation, physical discomfort, and anxiety in the educators in this studied case. We consider that this can be associated with monitoring and accompaniment developed by the different Higher Education Institutions to their educators. They managed to complete the different periods of the school year, digitize their content, and use different tools for synchronous and asynchronous communication.

It is noteworthy that the institutions and educators of the Dominican Republic have agreed on the importance of continuing work with their students in the pandemic. Planning for the possible reopening of universities, they have undergone a redesign and recovery process of their subjects or courses as well restructured to achieve a new model of the organization of learning teaching processes, thoroughly hybridized, improving the quality of services, taking advantage of the lessons learned during this period of the pandemic.

5.6. Panama

As of the announcement of the first case of COVID -19 in Panama on March 9th, 2020, economic and university activities were interrupted, until the National Government decreed a curfew and the confinement of the population. Universities began the closure of their facilities on March 13th. In Panama, the beginning of the semester is generally at the end of March. Classes were delayed in some universities for up to a month, and the reactivation of academic activities was possible through remote channels.

This work collected 20 responses mainly from educators from the province of Panama (65%) and countryside (35%), most of which were public universities (90%). Educators adapted their courses to the platforms recommended by the Technology Centers, accompanied by training, which facilitated the adoption since 66% had had previous contact with technological tools and distance courses. Similarly, a significant number (86%) maintained their classes, using technologies remotely.

Educators acquired equipment such as tablets and other devices to carry out their academic tasks. Many of them stated that they had computer equipment that they use exclusively for classes.

Educators experience increased physical discomfort and muscle pain (from 23% at the beginning to 38% in the last periods of the pandemic). In comparison, the lack of memory has not been significant (more than 80% state that they have not had a memory loss). Irritation and discouragement have not constituted a health threat, although 31% of educators answered that they begin to feel irritable and with feelings of apathy.

Educators express their dissatisfaction with workload (85% answered that they increased significantly), in the remote attention to students. 69% of educators respond that they take on many hours of work, coupled with domestic tasks at home. Consequently, 56% responded that they do not dedicate themselves enough to gratifying personal activities and have begun to experience loneliness.

Regarding the work environment, responses point out the inconveniences that occur during remote classes: excessive noise, inadequate real estate, and frequent distractions (69%). The most significant insecurity concerns student evaluation (38%); with a diversity of responses in other factors, such as applying ICT-mediated learning methodologies and psychological orientation at work. Educators perceive less insecurity with employment contracts (more than 54%). Regarding the relationship with the students, 54% answered they had perceived a slight or minimal decrease in motivation. Complaints in the dynamics of the classes have been very few with 56% of the educators.

5.7. Peru

On March 16th, Peru began to adopt compulsory confinement as a measure adopted by the government. At universities, the acceptance of the use of technologies for educational and pedagogical processes brought not only needs of a competitive nature, those concerning digital skills, but also logistical and equipment difficulties.

In the specific case of Peru, internet access is still a complex problem to solve. The internet is still a scarce resource in rural areas, so some students must travel a few hours to have connectivity. Another problem in the high Andean areas is that due to the nature of the geography (high hills and canyons), educators cannot get good Internet signals and, consequently, several times they are unable to teach. Thereby, educators and students have been affected because they have poor connectivity (García-Salirrosas, 2020), generating anxiety, despair, and stress (Cao et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020).

The results from Peru show that 52 surveys were answered mainly by educators from the department of Apurimac (55.8%), Lima (15.4%), Arequipa (9.6%) and other departments of the country (19.2%), most of which were public universities (71.1%). The most significant number of educators surveyed belong to the male gender (84.6%) and a minority to the female gender (15.4%). Most educators are aged between 40 and over (76.9%), and a minor part is under 40 years old (23.1). Therefore, they are educators with experience in teaching. Most of the educators work in the engineering area (69.6%), and they have master’s (46%) and Ph.D. (36%) degrees.

The educators changed teaching from face-to-face to remote. They have had to train in using tools for synchronous and asynchronous teaching. Something important to note is that several universities migrated to the free services offered by Google.

5.8. Uruguay

Uruguay (3,505,985 population) has 107,623 university students. The Universidad de la República (Udelar), comprises 99.4% of them, with around 150,000 active students and 11,500 educators. On March 16th, all face-to-face educational activities at Udelar were suspended, trying to continue higher education using digital platforms, providing some commercial solutions, in addition to the institutional Open Digital Ecosystem (VLE, multimedia and recorded video-lectures). During 2020 and part of 2021, all the activity was remotely developed through digital platforms.

Regarding the analysis of the survey carried out with educators and institutional studies (Dirección General de Planeamiento, 2020), there is evidence of perceived stress factors in the educational workers during the pandemic. According to the respondents’ profile, most of them are women (68.75%) from the capital Montevideo (93.26%), postgraduate (34.62%), aged 30 to 50 years (56.73%), from Health Sciences (54.32%), have less than ten years of university teaching experience (51.92%), and work 20 to 40 hours weekly (58.65%). During quarantine, they have spent most of the time with their family, children and/or partner (37.50%) isolated in their home, with an average of 2.8 people. Before the quarantine, 53.85% of them had already experienced remote teaching, but during quarantine this experience was extended up to 88.94%.

Considering the stress factors, “anxiety” (48.07%), “muscle and body aches” (42.31%), and “discouragement” (35.58%) are the most mentioned. 21.63% started to feel helplessness or frustration and were irritable (12.50%). Most educators experienced workload (54.33%), overlapping domestic and work tasks (53.3%) and lack of personal time (45.2%), similar to results in Dirección General de Planeamiento (2020): almost 74% of educators have felt overloaded in the performance of their tasks, 60% of educators said that care responsibilities increased and 77.9% of female educators had difficulty in combining work and care (70.2%).

Concerning self-perception of digital skills, results show a contrast in the management level compared to the difficulties encountered in using them in teaching during the COVID-19. The perceived digital skills level is medium or high for 77%, while 51% have had difficulties with digital tools and/or remote teaching methodologies. In those cases, they sought co-workers’ help (56.25%), same as in Dirección General de Planeamiento (2020): 74% of educators carried out remote teaching in the first semester in coordination with a teaching team. Educators also show digital competencies for the autonomous search for solutions, seeking support in internet tutorials (50%), and, to a lesser extent, they go to institutional technical support (36%).

Before the quarantine, 42.79% received training on technological tools for teaching through virtual learning environments, while during the pandemic this percentage rose to 51.92%. Internet access at home is adequate for 84.13% of educators, and 72.60% have equipment for exclusive use, and they are appropriate for all their work activities for 77.88% of them. Satisfaction levels found in the DGPlan (2020) show 75% of educators satisfied or very satisfied with the remote teaching experience of the first semester at Udelar.

5.9. Venezuela

In Venezuela, the national government decreed a “State of Alarm” on March 13th, 2020, and with this, the suspension of educational activities, initially for 30 days (Hernández et al., 2020). Subsequently, the Ministry of Popular Power for University Education (MPPEU) decreed the Home University Plan as a state policy and ordered educational organizations to adapt the teaching functions to the different pre-existing educational platforms. Still, it did not consider that in most of the country’s public universities the technological and connectivity infrastructure is highly precarious and even non-existent, as well as that of the population in general.

We obtained a total of 22 participants, among educators from different public universities concentrated in the center of the country (Aragua, Miranda, and Capital District states), whose responses were evenly distributed between both sexes. Of this population, five educators responded not having previous experiences with remote teaching-learning processes mediated by ICT. Likewise, only five of the respondents stated that they are not currently immersed in distance learning activities.

Besides, five professors do not have technological equipment for exclusive use or appropriate remote activities, since they must share them with the family group. Their activities must be carried out at inappropriate hours, which sometimes must be for rest and family enjoyment.

Only six educators indicated having access to an adequate Internet connection service to carry out activities, ratifying what is indicated in different studies (Fardoun et al., 2020; UNESCO, 2020). But only three educators expressed their refusal to pursue remote activities. Likewise, seven of those surveyed said they felt insecure and had difficulties regarding the proper management of the technologies and methodologies required to conduct remote teaching.

In addition to the above, ten educators expressed feeling irritated and discouraged about abruptly and disruptively facing a new modality in their daily teaching activities. Finally, thirteen said they were overwhelmed by excessive work and lack of personal time despite being confined to the home.

6. Overall Discussion

In general, educators of all countries —except the Dominican Republic—, reported suffering from some physical discomfort, such as muscle pain and body aches, and the occurrence of episodes of memory failure, irritation, discouragement, and anxiety. All these stress-related elements were linked, in some manner, to the professional activity of educators in remote teaching during COVID-19 pandemics. The reasons why these factors were not predominant in the Dominican Republic educators is a subject for further studies.

Respondents firmly pointed out gender-related aspects in many countries, namely Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Panamá, Uruguay, and Venezuela. When reporting a higher workload perception, this report was more frequent coming from women. Cultural aspects of the region, like the “macho culture”, make women more vulnerable to home office activities, due to the attention they are supposed to pay to housework. Due to the high domestic demands, the home environment is not appropriate for work, for some of them. This is a clear finding of inequalities related to gender and amplified by pandemic regulations.

Before the pandemic, technology was mainly considered a complement used in hybrid modalities, but it became the only means of teaching. In this context, other problems arise, such as the lack of training to carry out educational plans created for face-to-face modalities, to virtual modalities. In this sense, there are some interesting findings in the increase of stress symptoms related to using ICT tools for virtual learning. There is no clear relationship between the degree of technological expertise and stress factors. While educators with less expertise could feel insecure when using new technology, they tend to have fewer expectations than those who have a more significant experience with educational technology. Educators with less experience probably have a safe-easy approach to the problem: they use fewer tools more efficiently (i.e., WhatsApp sharing files, or videoconference recording the whiteboard), having less stress than those trying to use technology under a raised bar approach. However, in general, educators use more time to prepare classes and design and build resources, using the extra time to track students’ progress and homework review.

Most of the respondents reported having some previous experience in remote activities, mainly from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and Uruguay. However, no direct impact of these previous experiences on stress factors was clearly perceived. Besides, it is common sense that previous or continuous training for teaching technologies could help reduce the stress factors on educators. Still, Brazilian and Colombian educators reported no relationship among these aspects.

Due to this specific universe of individuals studied, most of them had access at least to basic technological infrastructure for remote teaching. Most of them lived in bigger cities, whose infrastructure is usually better than smaller towns. However, some fundamental infrastructure problems appeared in some responses, either due to country economic reality - as reported by Venezuelan educators, which mentioned electricity and internet cuts in their country - or geographic conditions - as found in responses from Andean educators, mainly from Peru, since these high-altitude places suffer from poor Internet access.

7. Conclusions

The pandemic resulting from COVID-19 has brought about profound changes for the whole of society, both social and professional context. We have witnessed interaction and communication technologies undergo a significant increase in practically all social and professional activities. Teaching and learning processes also underwent substantial changes in this period, supported by digital technologies. Work, technology, and stress started to live in educators’ homes worldwide.

This paper discusses issues leading to educators’ stress related to the adoption of remote educational practices during the pandemic COVID-19 in the context of Latin American higher education. The study sought to verify educators’ perception of signs and symptoms related to stress associated with the period of social isolation.

Our main findings are that with just one exception —the Dominican Republic— educators of all countries reported suffering from some stress-related aspects, linked in some manner, to remote teaching during COVID-19 pandemics. A more frequent report coming from women is related to higher workload perception, unfolding gender inequalities, amplified during pandemics. There is no clear relationship between the degree of technological expertise and stress factors, although, in general, educators use more time to prepare learning material and to track students’ progress. Technological infrastructure was not a big concern for those educators in big cities, but some fundamental infrastructure problems were reported either due to the country’s economic reality or geographic conditions.

The substitution of face-to-face classes with classes mediated by technology had so far extended its term in all the Latin American countries studied in this survey. This indicates that the challenges overcome by educators for this transition will serve as a basis for continuing these activities in the coming future, influencing the digital transformation in Education, as appointed by Ramírez-Montoya (2020) and García-Peñalvo (2021). However, many challenges remain on the agenda which, combined with the scenario of uncertainty provided by the pandemic, will continue to bring doubts and anxiety, triggering stress —for instance, the assessment process in hybrid contexts is still a subject under research, as pointed out by García-Peñalvo et al. (2021b). All these factors may lead to demotivation, physical problems and emotional changes that will compromise the quality of the teaching-learning process and, at the limit, educators’ health.

This work contributes to the body of knowledge under construction about our experiences during the pandemic of the new coronavirus, a singular moment in history, in registering part of the scenario perceived by higher education educators in Latin America. Future work can be developed to follow these results, carrying out new surveys to understand the evolution of the perception of stress among educators. In addition, this work can awaken new initiatives of research projects and actions to reduce the stressors found in this study.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the collaboration of all educators in Latin America who kindly gave up part of their time to respond to this survey about stress in the COVID-19 pandemic period.

References

Araujo, R. M., Cibelle, A., Martins, V. F., Eliseo, M. A., & Silveira, I. F. (2020). COVID-19, mudanças em práticas educacionais e a percepção de estresse por docentes do ensino superior no Brasil [COVID-19, changes in educational practices and the perception of stress by higher education teachers in Brazil]. Revista Brasileira de Informática na Educação, 28, 864–891. https://doi.org/10.5753/rbie.2020.28.0.864

Calais, S. L., Andrade, L. M. B. y Lipp, M. E. N. (2003). Diferenças de sexo e escolaridade na manifestaçao de stress em adultos jovens. Psicología: Reflexâo e Crítica, 16(2), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722003000200005

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, Article 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Casali, A., & Torres, D. (2021). Impacto del COVID-19 en docentes universitarios argentinos: cambio de prácticas, dificultades y aumento del estrés [Impact of COVID-19 on Argentine university teachers: change in practices, difficulties and increased stress]. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnología en Educación y Educación en Tecnología, 28, 423–431. https://doi.org/10.24215/18509959.28.e53

COAD. (2020). Balance y prospectiva sobre nuestro trabajo en el contexto de pandemia [Balance and perspective on our work in the context of the pandemic]. Association of Teachers and Researchers of the National University of Rosario. http://www.coad.org.ar/

Dirección General de Planeamiento (2020). Principales resultados de la Encuesta a docentes de la Udelar sobre la propuesta educativa en la modalidad virtual del primer semestre de 2020, Universidad de la República [Main results of the Survey of Udelar teachers on the educational proposal in the virtual modality of the first semester of 2020, University of the Republic]. https://bit.ly/3Yazdmw

Fardoun, H., González, C., Collazos, C. A., & Yousef, M. (2020). Exploratory study in Ibero-America on teaching-learning processes and evaluation proposal in times of pandemic. Education in the Knowledge Society, 21, Article 17. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23537

García-Holgado, A., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2022). A Model for Bridging the Gender Gap in STEM in Higher Education Institutions. In F. J. García-Peñalvo, A. García-Holgado, A. Dominguez, & J. Pascual (Eds.), Women in STEM in Higher Education. Good Practices of Attraction, Access and Retainment in Higher Education (pp. 1–19). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1552-9_1

García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2021). Digital Transformation in the Universities: Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education in the Knowledge Society, 22, Article e25465. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.25465

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Corell, A., Rivero-Ortega, R., Rodríguez-Conde, M. J., & Rodríguez-García, N. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 on Higher Education: An Experience-Based Approach. In F. J. García-Peñalvo (Ed.), Information Technology Trends for a Global and Interdisciplinary Research Community (pp. 1–18). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-4156-2.ch001

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Corell, A., Abella-García, V., & Grande-de-Prado, M. (2021b). Recommendations for Mandatory Online Assessment in Higher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In D. Burgos, A. Tlili, & A. Tabacco (Eds.), Radical Solutions for Education in a Crisis Context. COVID-19 as an Opportunity for Global Learning (pp. 85–98). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7869-4_6

García-Peñalvo, F. J., García-Holgado, A., Dominguez, A., & Pascual, J. (Eds.). (2022). Women in STEM in Higher Education. Good Practices of Attraction, Access and Retainment in Higher Education. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1552-9

García-Salirrosas, E. E. (2020,). Satisfaction of university students in virtual education in a COVID-19 scenario. In 2020 3rd International Conference on Education Technology Management (pp. 41–47). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3446590.3446597

Gómez-Gómez, M., Hijón-Neira, R., Santacruz-Valencia, L., & Pérez-Marín, D. (2022). Impact of the Emergency Remote Teaching and Learning Process on Digital Competence and Mood in Teacher Training. Education in the Knowledge Society, 23, Article e27037. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.27037

Goren, N., Jerez, C., & Figueroa, K. Y. (2020). ¿Los cuidados en agenda?: Reflexiones y proyecciones feministas en época de COVID-19. Desigualdades en el marco de la pandemia: Reflexiones y desafíos (pp. 33–43). EDUNPAZ.

Goulart Junior, E., & Lipp, M. E. N. (2008). Estresse entre professoras do ensino fundamental de escolas públicas estaduais [Stress among teachers of fundamental education in state public schools.]. Psicologia em estudo, 13(4), 847–857. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722008000400023

Hernández, C., Garcés, M. F., & Hernández, E. (2020). Pandemia de COVID-19 en Venezuela: Segunda cuarentena. Acta Científica De La Sociedad Venezolana De Bioanalistas Especialistas, 23(1), 118–130.

Hew, K. F., Jia, C., Gonda, D. E., & Bai, S. (2020). Transitioning to the “new normal” of learning in unpredictable times: pedagogical practices and learning performance in fully online flipped classrooms. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1) 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00234-x

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, Article 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2021). Corrigendum to Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey [Psychiatry Research, 288 (2020) 112954]. Psychiatry research, 299, Article 113803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113803

Knopik, T., & Oszwa, U. (2021). E-cooperative problem solving as a strategy for learning mathematics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education in the Knowledge Society, 22, Article e25176. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.25176

Lizana, P. A., Vega-Fernadez, G., Gomez-Bruton, A., Leyton, B., & Lera, L. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teacher Quality of Life: A Longitudinal Study from before and during the Health Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), Article 3764. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073764

Martins, M. D. G. T. (2007). Sintomas de stress em professores brasileiros [Symptoms of stress in Brazilian teachers]. Revista Lusófona de Educação, 10, 109–128.

Monteiro, B. M. M., & Souza, J. C. (2020). Saúde mental e condições de trabalho docente universitário na pandemia da COVID-19 [Mental health and working conditions for university teachers in the COVID-19 pandemic]. Research, Society and Development, 9(9) e468997660–e468997660. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i9.7660

Novaes, F. C., & Aquino, S. D. D. (2021). Mundo post pandémico: Consecuencias individuales y políticas de la pandemia de COVID-19 [Post-pandemic world: Individual and political consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic]. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 26(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20210002

Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia, M. J., & de Luis-García, R. (2020). Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Research, 290, Article 113108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Berasategi Santxo, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., & Dosil Santamaría, M. (2021). The psychological state of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis: The challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 3861. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.620718

Pather, N., Blyth, P., Chapman, J. A., Dayal, M. R., Flack, N. A. M. S., Fogg, Q. A., Green, R. A., Hulme, A. K., Johnson, I. P., Meyer, A. J., Morley, J. W., Shortland, P. J., Štrkalj, G., Štrkalj, M., Valter, K., Webb, A. L., Woodley, S. J., & Lazarus, M. D. (2020). Forced Disruption of Anatomy Education in Australia and New Zealand: An Acute Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1968

Pereira, H. P., Santos, F. V., & Manenti, M. A. (2020). Saúde Mental de Docentes em Tempos de Pandemia: os impactos das atividades remotas [Mental Health of Teachers in Times of Pandemic: the impacts of remote activities]. Boletim de Conjuntura (BOCA), 3(9), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3986851

Pedrozo-Pupo, J. C., Pedrozo-Cortés, M. J., & Campo-Arias, A. (2020). Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia: an online survey. Cadernos de saúde publica, 36, Article e00090520. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00090520

Poalses, J. & Bezuidenhout, A. (2018). Mental Health in Higher Education: A Comparative Stress Risk Assessment at an Open Distance Learning University in South Africa. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i2.3391

Rajkumar R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian journal of psychiatry, 52, Article 102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2020). Digital transformation and educational innovation in Latin America in the framework of COVID-19. Campus virtuales, 9(2), 123–139.

Robinet-Serrano, A. L., & Pérez-Azahuanche, M. (2020). Estrés en los docentes en tiempos de pandemia COVID-19 [Stress in teachers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic]. Polo del Conocimiento, 5(12), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v5i12.2111

Rodríguez-Paz, M. X., González-Mendivil, J. A., Zárate-García, J. A., Zamora-Hernández, I., & Nolazco-Flores, J. A. (2021). A Hybrid Teaching Model for Engineering Courses Suitable for Pandemic Conditions. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologías del Aprendizaje, 16(3), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1109/RITA.2021.3122893

Sadir, M. A., Bignotto, M. M., & Lipp, M. E. N. (2010). Stress e qualidade de vida: influência de algumas variáveis pessoais [Stress and quality of life: influence of some personal variables]. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 20(45), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2010000100010

Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus, 12(4), e75411. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

UNESCO. (2020). COVID-19 Impact on Education. Retrieved Abril 8 from https://bit.ly/2yJW4yy

UNICEF (2020) ¿Cómo están afrontando los docentes la crisis del COVID-19? [How are teachers coping with the COVID-19 crisis?] http://bit.ly/3X5BrT0

Zeeshan, M., Chaudhry, A. G., & Khan, S. E. (2020). Pandemic Preparedness and Techno Stress among Faculty of DAIs in COVID-19. Sir Syed Journal of Education & Social Research (SJESR), 3(2), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.36902/sjesr-vol3-iss2-2020(383-396

_______________________________

(*) Autor de correspondencia / Corresponding author